The case of DC Comics v Mark Towle 2:11-cv-03934-RSWL-OP (accessible here) dealt with the copyright protection of the Batmobile, ever-present in the Batman saga, and its infringement through the making of replicas of specific versions of the aforementioned Batmobile [of the full-size variety, not merely toys]. As exclaimed by judge Ikuta, delivering the court's judgment; Holy copyright law, Batman!

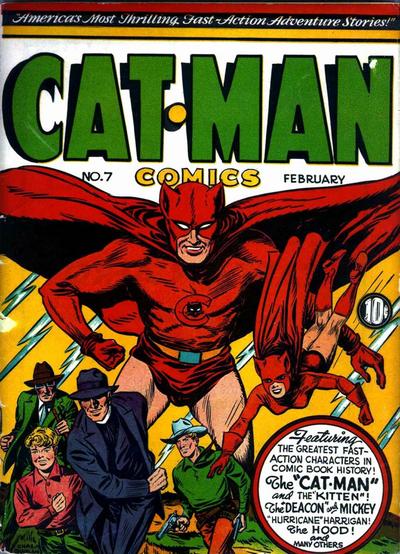

| Quickly, to the Katmobile! |

The first claim dealt with by judge Ikuta was whether the Batmobile would be afforded copyright protection under US law ["to the Batmobile!" she exclaimed].

Through an extensive discussion of precedent surrounding comic book characters and protection afforded to them, judge Ikuta laid down a three-part test in assessing whether a character (or in this case, vehicle) would be afforded copyright protection. First, the character must generally have physical as well as conceptual qualities [meaning it has to not simply be a literary idea, but manifest itself in a physical and/or conceptual manner, such as in images, movies etc.]; second, the character must be sufficiently delineated to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears [this need not be in terms of appearance, but through their character, personality etc.]; and third, the character must be especially distinctive and contain some unique elements of expression [in other words, not be a generic character with generic elements in their representation].

|

| Some Kats have a secret alter-ego... |

As a final step the Court looked at whether Mr. Towle's replicas had in fact infringed on DC Comics' rights in the Batmobile. Both parties had no contentions over whether the cars were actual replicas of the two versions of the Batmobile. Mr. Towle argued that, as the Batmobiles features in the 1989 movie and the 1960s TV show were derivative works, he did not infringe on DC's rights in the underlying work. Judge Ikuta quickly dismissed this, stating that "...if the material copied was derived from a copyrighted underlying work, this will constitute an infringement of such work regardless of whether the defendant copied directly from the underlying work, or indirectly via the derivative work". No rights were transferred as a part of the licence agreements for the two derivative works, and therefore Mr. Towle had infringed DC's copyright through making his replica vehicles. This was deemed to be the case even though the two versions of the Batmobile differed from their depiction in the comic books.

The case was an interesting one, at least to this Kat. The Batmobile has been depicted in a variety of forms over the years, and when comparing the Batmobile in the recent Dark Knight movie, and, for example, the 1960s TV show version, it is hard to say they are cut from the same cloth. Even so, based on a US law argument the decision seems right [although this Kat invites anyone who might disagree to let him know why], and as judge Ikuta ended, quoting Batman: "[i]n our well-ordered society, protection of private property is essential".

![[GuestPost] G1/24: Tuning in! A take on the state of proceedings before oral proceedings](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjZhEivE5bp7QOwZsyZXAXbVNYSmLjUthkB2Q7fm1_dpB97u5lIQeyWT9ZadUTAH3Z-hXn13VpW4vBDRPx9emCnoDV6tbUTkyvfmqPv1nNInL8XMdrAtSZ2hcRQr2LjxKovC9wTk_XyZxQ0CtX1MUrO_Muz3OJ4ld8AftymsdUmKD7xNksYMwk6/s150/Picture%201.png)

![[Guest post] ‘Ghiblification’ and the Moral Wrongs of U.S. Copyright Law](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhxl1BQBAW3Y-asjb1xXB9eA4DYy77fky6WgR-prC-_6DeBbDqOgCUDWyiz0Q3B23MWWAXnkbS2H2js7OUwA0JQXAHmsyVFgGIHeJz7zJ791vTzOD-4SJqWFIuywFXQyd3ahybbdZd4e8IEVfcNqctvyR8lumv_Gix6Tsw5cSvbHpTI1nwvztDuAQ/s150/IMG_2179.HEIC)

![[Guest book review] The Handbook of Fashion Law (with a discount code)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgB4h2AdqJKwq9O3Ft4Mb7C39tv_NeFpkzrOfvhIsuwAkM_ops2Hgj7fdwzq_TQsjQDvQrQa-yyC9Q9pNiugseXRlUaMdsr_cmYUbh9lH8HDECMCbsTuNboVgpafyEhkgDkVS6ruHkuz8Sx0QVGI_1S8R9kbsHdNIYrRjqhyphenhyphen010_txjJUYvlZOtWA/s150/Fashion%20Law%20Book%20Bicture.jpg)

Maybe I'm just having a sense-of-humour failure today, but I find the judge's levity rather inappropriate. It can't have done much to ease Mr Towle's pain to know that the judge was having so much fun while she handed down judgement against him.

ReplyDeleteI think the US jurisprudence has really lost its way on the protection of literary characters. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1954 (Warner Bros v Columbia Broadcasting System 216 F.2d 945) seems to have had a much better grip on the fact that copyright subsists in works as such. The question whether the copying of a character infringes is a question of infringement, not subsistence. I am uncomfortable with characters ever being protected as such, but presumably it cannot be excluded. However, in this case the works in question were artistic works (the two very different designs for the Batmobiles) to which (no doubt) DC Comics could show no title, as they will have been created by the TV production company. One might further ask: which work was infringed by copying the "character" and when does the term expire? In fact, the court protected the idea of a Batmobile, which would not be protectable even if it were a literary work. I regret that I also found the judge's frivolity tiresome, but perhaps my sense of humour was affected by my disapproval of the legal reasoning...

ReplyDeleteA blogpost on Bat-mobiles is a quite refreshing diversion from Bat-tistelli. ;-)

ReplyDelete