On the patent track, the first session at the Fordham IP Conference brought news of developments at the US Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”), moderated by Robert J. Goldman (Ropes & Gray LLP (Ret.), Silicon Valley). With the AmeriKat ensconced in the FRAND panel session (report here), Kat friend and Fordham guest Kat, Amy Crouch (Simmons & Simmons) covered the PTAB panel.

Over to Amy:

"First to present was Vanessa Bailey (Intel Corporation, Washington, D.C) on “Fostering Innovation Through IPRs: The Corporate Perspective”. The USPTO receives over half a million patent applications and issues over 350,000 patents a year. Examiners have limited time to find and review available prior art and many categories of prior art (e.g. commercial products and various types of publications) are not even readily accessible to the examiner. So it is inevitable that some egregious patents will be issued.

The PTAB has a panel of 3 or more administrative patent judges with extensive technical and patent law experience and greater resources, along with the benefit of prior art searching and advocacy by the parties. Vanessa then dealt with various myths about inter partes review (“IPR”) challenges at the PTAB (see above, right and below, left).

In Vanessa’s view, patents being invalidated by the IPR process is saving the judicial system from being overburdened and she detailed two examples of “bad” (or "invalid") patents being prevented from damaging US businesses due to successful IPR petitions. She concluded that “to remain competitive, we need to support the use of IPRs!”

Next, Patricia A. Martone (Law Office of Patricia A. Martone, P.C., New York) presented on “Recent changes to PTAB IPR practice, how far do they go and who do they help?” Director Iancu has sought reform in the USPTO, essentially to change the notion that it is where patents go to die and make the system more predictable. He is ultimately restrained by statute and Supreme Court precedent, in particular the fact that the PTAB has a binary choice to either to institute review of all challenged claims or none (SAS Institute v Director Iancu, 2018).

The USPTO also added the additional requirement that an IPR had to be instituted, not only on all claims raised, but also on all patentability challenges appearing in the petition. In other words, this results in an estoppel impact on District Court proceedings in relation to any ground that “reasonably could have been raised”. Effectively all prior art challenges will be brought in the PTO because of the effect of this estoppel issue. It is an interesting question as to what exactly the jury will be told if a patent has found to be valid in IPR proceedings, if anything. Should they simply be told that the claims are valid and left only to consider questions of infringement and damages?

Another change in the past year is proposed new rules for claim amendments. Even though a motion to amend claims in IPR proceedings was provided for in the America Invents Act (“AIA”), in practice motions to amend were rarely granted primarily because PTAB proceedings must be completed within one year. The USPTO have now instituted a pilot program which provides two new options for patent owners: seeking preliminary guidance from PTAB and the opportunity to file a revised motion to amend. In Patricia’s view amending claims will still be very difficult, but it is important that patent owners can do this – ultimately “if a patent is important to protect your business then you want to save it for the future”.

Panellist Dustin F. Guzior (Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, New York) commented that since SAS he had already seen parties coming up with highly creative arguments as to why prior art should still be allowed into court proceedings. One such argument that has been made is that it can still be relevant in the context of evaluating the difference an invention has made over the prior art and therefore feeds into the question of damages.

Fellow panellist John Pegram (Fish & Richardson, P.C., New York) suggested that two housekeeping amendments to the AIA would be useful: (1) reversing the SAS decision to permit IPRs in respect of only some of the claims and (2) to change the post grant review (“PGR”) estoppel procedure. Are either of these a good idea?

Vanessa was not in favour of (1) as it would make the estoppel less certain and thought that (2) was not necessary as, in her view, the reason IPRs are not used is not because of estoppel, but rather because of timing issues. In her view, the estoppel position has not actually changed much since SAS as parties would always have assumed they were going to be estopped in lots of cases anyway. Dustin wondered if it could result in more “garbage” patents being dealt with in court because it is simply not possible to get all “good” prior art into an IPR? Patricia commented that ultimately what parties want is a patent system that gives rise to the statutory presumption of validity and that would pave the way for more patents to be filed.

Robert asked if the IPR system was affecting innovation and R&D? Vanessa said that from her standpoint it had not. Intel have a huge number of patents and also file lots of IPRs. There has been a lot of important innovation since AIA - blockchain and AI to name but a couple of key areas, and the PTAB is important for getting rid of the “low hanging fruit” in terms “bad” patents. That is the whole point of it.

Panellist George E. Badenoch (Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, New York) agreed with John’s amendment (2) for changing the PGR estoppel procedure because “often you simply do not know what the best prior art is until you see how the claims are to be construed and asserted”. The factors originally set out in the Georgia Pacific test are drafted to catch everything relevant in a trial and they need be reigned in. Dustin commented that, in particular, parties would not want the jury to see the PTAB decision in case it gives the impression that the patent just “squeaked through” that assessment.

George then turned to his presentation on “Standing, Privity and Estoppel in IPR Proceedings”. Whilst to file a trade mark opposition there is a requirement that you reasonably believe you will be damaged, when it comes to IPRs it is now clear that there is no standing requirement. All “real” parties do need to be named, and there are the estoppel provisions to prevent re-litigation, but is that enough to prevent patentees from vexatious actions? Anyone, including public interest petitioners can challenge validity. But, if they lose, then they cannot appeal to the Federal Circuit because that does require standing. There are now even companies set up to file IPRs solely for stock market manipulation purposes. This has been upheld simply because there is no standing provision, but you have to doubt that that is what Congress intended!

In relation to privity, the recent AIT v RPX (2018) Federal Circuit case has confirmed that the court will look behind the parties into what is really going on. In that case, two parties (Salesforce and RPX) brought successive petitions, the latter after the first had been rejected. Salesforce was in fact a member of RPX. The Federal Circuit commented that “determining whether a non-party is a “real party in interest” demands a flexible approach that takes into account both equitable and practical considerations, with an eye toward determining whether the non-party is a clear beneficiary that has a pre-existing, established relationship with the petitioner.” The appeal in this case is happening at the moment.

Robert asked about stays of proceedings. Patricia commented that, as the latest statistic from the PTAB was ~63% finding of invalidity, it would seem likely that courts would grant stays. Panellist Brian P. Murphy (Haug Partners LLP, New York) agreed, noting that because estoppel now has “more teeth”, stays are more likely to be granted.

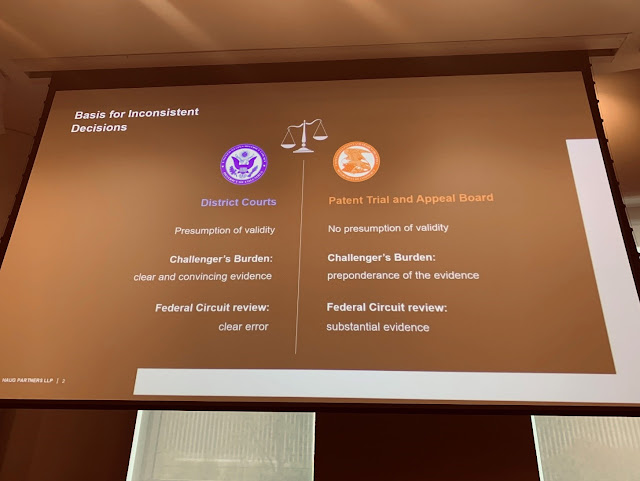

Brian then turned to his presentation, “Dueling Banjos – When Does a PTAB Invalidity Decision Unwind a District Court Infringement Judgment?” The AIA sows the seeds for inconsistent decisions on validity. Some of the key differences that underlie this are as follows:

|

In the PTAB the burden of proof is lower, and in close cases, that does make a difference. In the case of Novartis v Noven (Federal Circuit 2017), two district courts found the patent to not be invalid, whereas the PTAB later found it invalid, quoting Supreme Court case law that the “different evidentiary burdens mean that the possibility of inconsistent results in inherent to Congress’ regulatory design”.

When is the judgment “final” in the sense that it has a preclusive effect? In the case of Fresenius v Baxter (Federal Circuit 2013), the issue of damages was outstanding when the PTAB invalidated the patent. The court, quoting the Supreme Court, found that a “final decree is one that finally adjudicates upon the entire merits, leaving nothing further to be done except the execution of it”. In that case the decision was not “final” and so damages did not need to be paid.

Notably, Judge Newman dissented, stating that “failure to adhere closely to basis issue preclusion… is most likely to lead directly to inconsistent results that… undermine confidence in the judicial process” and “the loser in this tactical game of commercial advantage and expensive harassment is the innovator and the public”. This was all of course an issue of timing because if the judgment was “final” (i.e. also dealing with post-verdict damages) then damages would have had to have been paid.

The system allows such “accidents of timing” and the same may well happen in the ongoing VirnetX v Apple cases to the effect that Apple may end up not having to pay a billion dollar judgment!

From the audience Klaus Grabinski (Federal Court of Justice, Karlsruhe) commented that in Germany there is a presumption of validity and it is for the claimant to show invalidity. Once there is a final court decision on infringement, the claimant can get damages awarded and paid. Then if the patent is revoked, the other party has one month to come back to the infringement court with a restitution claim. "

Fordham 27 (Report 13): PTAB

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Thursday, May 02, 2019

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Thursday, May 02, 2019

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Thursday, May 02, 2019

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Thursday, May 02, 2019

Rating:

![[GuestPost] G1/24: Tuning in! A take on the state of proceedings before oral proceedings](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjZhEivE5bp7QOwZsyZXAXbVNYSmLjUthkB2Q7fm1_dpB97u5lIQeyWT9ZadUTAH3Z-hXn13VpW4vBDRPx9emCnoDV6tbUTkyvfmqPv1nNInL8XMdrAtSZ2hcRQr2LjxKovC9wTk_XyZxQ0CtX1MUrO_Muz3OJ4ld8AftymsdUmKD7xNksYMwk6/s150/Picture%201.png)

![[Guest book review] The Handbook of Fashion Law (with a discount code)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgB4h2AdqJKwq9O3Ft4Mb7C39tv_NeFpkzrOfvhIsuwAkM_ops2Hgj7fdwzq_TQsjQDvQrQa-yyC9Q9pNiugseXRlUaMdsr_cmYUbh9lH8HDECMCbsTuNboVgpafyEhkgDkVS6ruHkuz8Sx0QVGI_1S8R9kbsHdNIYrRjqhyphenhyphen010_txjJUYvlZOtWA/s150/Fashion%20Law%20Book%20Bicture.jpg)

![[Guest post] ‘Ghiblification’ and the Moral Wrongs of U.S. Copyright Law](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhxl1BQBAW3Y-asjb1xXB9eA4DYy77fky6WgR-prC-_6DeBbDqOgCUDWyiz0Q3B23MWWAXnkbS2H2js7OUwA0JQXAHmsyVFgGIHeJz7zJ791vTzOD-4SJqWFIuywFXQyd3ahybbdZd4e8IEVfcNqctvyR8lumv_Gix6Tsw5cSvbHpTI1nwvztDuAQ/s150/IMG_2179.HEIC)

No comments:

All comments must be moderated by a member of the IPKat team before they appear on the blog. Comments will not be allowed if the contravene the IPKat policy that readers' comments should not be obscene or defamatory; they should not consist of ad hominem attacks on members of the blog team or other comment-posters and they should make a constructive contribution to the discussion of the post on which they purport to comment.

It is also the IPKat policy that comments should not be made completely anonymously, and users should use a consistent name or pseudonym (which should not itself be defamatory or obscene, or that of another real person), either in the "identity" field, or at the beginning of the comment. Current practice is to, however, allow a limited number of comments that contravene this policy, provided that the comment has a high degree of relevance and the comment chain does not become too difficult to follow.

Learn more here: http://ipkitten.blogspot.com/p/want-to-complain.html