On a classically cool and cloudy San Francisco morning, after an invigorating 7:30AM AIPPI meeting, the AmeriKat worked her way to the first panel session of the at the World AIPPI Congress. This is the first in-person Congress since London hosted in 2019, so it was only apt that the first panel session was on the topic of IP and Covid-19. Although she could not stay for the entire session due to pressing issues developing in ExCo related to the moral rights question, she was there for the most pertinent discussion of interest to readers. Is IP to blame for access to Covid-19 vaccines?

Wolf also pointed the audience to the WTO Staff Working Paper which analyzed data of 10 Covid-19 vaccines and the related patent information on 74 patent families filed by 20 entities in 105 jurisdictions. The study found that patenting was the most important for the mRNA platform, but most of the patents for the mRNA vaccines were filed a significant number of years before Covid in around 2013. The same trend applied for the viral vector(s), save for a small peak in 2020/2021.

Eric Solwy (Partner, Sidley Austin) said that the role of IP is not a theoretical question in developing and incentivizing technology. The mRNA technology was discovered in 1961 and for many years private industry invested in developing the technology into something that could ultimately be useful at “great risk of that investment”. Moderna, for example he said, before going public in 2018 had raised over $2b in investment in funding and by September 2018 they had an accumulated deficit of hundreds of millions of dollars with some analysts forecasting that those loses could never be recouped. So looking at the history of the risks that companies were taking, there was a real and present risk of companies not being able to recoup those R&D costs. IP intervenes to alleviate this risk and incentivize invention. But it is not just the incentives for innovation, but also the collaboration between companies that IP fosters. Eric highlighted the Pfizer/BioNTech collaboration as one such example. Eric relayed that an executive of Pfizer had commented that although the executive was not able to speak for BioNTech, they could not imagine that BioNTech would have been comfortable sharing their proprietary mRNA innovations without IP protection having been in place.

Ernest Kawka (Deputy VP, PhRMA) recapped the timeline of the Covid-19 pandemic, pointing to 11 January 2020 when Chinese scientists shared the sequence of Covid-19. From here we saw numerous research collaborations which were part of a massive innovation response from not just pharma and biotech, but also tech. In December 2020, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization for the first vaccine – 11 months from the genetic sequence to the first authorized counter measure vaccine. This is a miraculous timeline. We may all appreciate that, but it is not always well digested of how quick this timeline is which was made possible with the global partnerships at which IP was integral. It culminated in 68% of the world having received at least 1 dose – 14 billion doses. Supply capacity far outstrips the demand for the vaccines. Real problems do exist, but stepping back the issues are not IP issues – they are other issues.

Maximillian Haedicke (Professor, University of Freiburg) teaches patent classes with students who are mainly patent sceptics but this year they have started to realize what IP incentivization was about, the impact of the waiver and why IP is important to vaccine development. Without IP, vaccine development would not have happened so quickly. When you look at the countries who develop the vaccines quickly, they come from countries with strong protection. This shows that the system works.

Wolf explained that a significant amount of money was invested by governments in the development of a COVID vaccine (which, Ernest commented, mostly consisted of advanced purchases). Thus, the question was raised as to the role of IP in those inventions which were supported by government funds. The EU Commission decision on procuring COVID-19 vaccines on behalf of Member States (2020) 4192 final (Annex) stated that they would promote IP sharing especially when such IP has been developed with public support. As to waiving IP, one question Wolf posed for the panel was whether an opportunity may have been missed because there was not conditionalities of IP availability linked to public funding.

Eric stated that most of the public funding when COVID-19 began circulating was for procurement of the vaccine, not R&D. Under US law, there is a distinction made between R&D contracts and a procurement contract (explained neatly in the Airbus/Boeing 353 WTO panel report under Bayh-Dole regime). In an R&D contract, the government has certain use rights and they have a marching right which is an extraordinary right (although it has never been exercised) where if the US Government has funded innovation which lead to a patent they can force the innovator to licence to third parties. A procurement contract does not.

Ernest explained that WTO waivers are not a new idea. Although 60 odd countries supported the waiver, the 35 Least Developed Countries who supported the waiver are exempt from the IP protection obligations under TRIPS. So it is important not to target IP as the culprit for the issues of vaccine access.

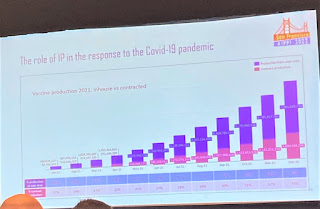

Wolf returned to the IP incentivization topic, but noted there was also the important “access” to vaccine issue. There have been outright compulsory licenses, including from Israel (18 March 2020), Hungary (17 May 2020) and the Russian Federation (31 December 2020). Germany and Canada took preparatory measures to enable government use if necessary. From the private sector, there was an open Covid-19 pledge where technology companies grant licenses to all their patent rights until 1 January 2023. So there seems, Wolf posited to the panel (at least superficially from an outsider's perspective), some recognition by these countries and companies that IP may be a barrier to access. Wolf then pointed to some data that looked at the overall production in 2021 and what share of that was under contract (and thus IP licensed). The production that was contracted out rose, but at a lesser rate.

Ernest said that in a normal, non-pandemic scenario to get from start to finish of an approved product is about 10 years, not including successfully launching the market globally. But to do this all in less than a year is extraordinary. One way to accelerate the launch of these products are these policies (being the Covid-19 pledges) that industry rely on, such as voluntary licensing and non-assertion positions and pricing pledges (e.g., a number of vaccines are provided at cost). On whether these pledges indicated that there was concern or were a reaction that there were IP barriers on the horizon, Ernest did not agree. His view was that it was a response to the rapid need to get the vaccines out which depended on partnership. The WTO prepared a document that listed the barriers to access to vaccines which pointed to the lack of expedited positions for importation, tax and tariffs (some countries still impose tariffs on vaccines and medicines), difficult and time-consuming regulatory approval processes and getting products like syringes through border controls. We know what the problems to vaccine access actually are as they have been studied. The problems are not IP; IP is the solution in terms of fostering collaboration.

Maximillian reminded the audience that the little brother to IP is market authorization. It is wrong to think that lowering IP protection means the vaccines would be automatically and immediately available, it would not because they still have to be authorized. IP should not be the scapegoat for the real problems.

Let the debate commence.

AIPPI Congress (Report 1): Is IP the "bogeyman" in access to Covid-19 vaccines?

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Rating:

Reviewed by Annsley Merelle Ward

on

Sunday, September 11, 2022

Rating:

![[Guest post] EUIPO Second Board of Appeal refers case to Grand Board of Appeal following earlier refusal to register a photograph of a man’s head/face as an EU trade mark](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiUj9v-k3DYaSVMR4lsmKDLHVB5nIoINuvZNbH2TQCelrfaAE9qmGSAQs-plzQ7HnZ7Svk_gRdrIODp0Nat5vpWajduit3xkArNhK76AHhX770RIJ62thfCVI5fnvcXU-5zH4NkUSfPY9FjRMFiK7OKJ7m7YSo2FzhyPSoA8ZWCsxaOXb0bBCoPQA/s72-c/Picture%201.png)

![[Guest post] Benelux Office rules on opposition proceedings prepared by ChatGPT](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi29VY0rNNP1Hqyz8RgB47r4q7fhqQfYHxsEbX_RKmT4KU5Y_vg7vB6dsAW91CidjMfJ38klTvD4mMtZb3QmwFPAHaGF88BPttWSbfYvo7UUg7MpFRTNtEjThmG0QaX2qZFFHSnN71i3YQZSBFC0SL7PgkAlme-XH8cSNWRFbOAOuLr_LMOGcImLQ/s72-c/Screenshot%202024-12-04%20at%2020.45.58.png)

No comments:

All comments must be moderated by a member of the IPKat team before they appear on the blog. Comments will not be allowed if the contravene the IPKat policy that readers' comments should not be obscene or defamatory; they should not consist of ad hominem attacks on members of the blog team or other comment-posters and they should make a constructive contribution to the discussion of the post on which they purport to comment.

It is also the IPKat policy that comments should not be made completely anonymously, and users should use a consistent name or pseudonym (which should not itself be defamatory or obscene, or that of another real person), either in the "identity" field, or at the beginning of the comment. Current practice is to, however, allow a limited number of comments that contravene this policy, provided that the comment has a high degree of relevance and the comment chain does not become too difficult to follow.

Learn more here: http://ipkitten.blogspot.com/p/want-to-complain.html