When can an artwork be

registered as a trade mark? The question is not an easy one, and may be

complicated further by consideration that the artwork at hand may be no longer

eligible for copyright protection due to the expiry of the term of protection.

This means that the question may turn out to be not just one relating to the

requirements for trade mark registration, but also involve broader, public

interest considerations that relate to the opportunity to continue protecting

by means of other IP regimes items (works) in relation to which the primary IP right

(in this case, copyright) is no longer available.

Background

On consideration that a

number of artworks by Norwegian artists [notably Gustav Vigeland] would soon enter the public domain under the Norwegian Copyright Act, the Oslo Municipality

(which manages several of these copyrights) is seeking to register a number of

artworks as trade marks.

The Norwegian

Industrial Property Office (NIPO) rejected some applications tout

court, holding that the signs at issue lacked distinctive character or

consisted of a shape that adds substantial value to the

goods [Article 3(1)(b)-(c)-(e) of

the Trade Mark Directive], while in

respect of other applications registration was granted for certain types of

goods and services.

The Oslo Municipality

appealed the decisions to the Board of Appeal, which - in addition to the

grounds considered by NIPO

– wondered whether registration should be also refused

on grounds of public policy and morality [Article 3(1)(f) of the Trade Mark Directive]. More specifically, the Board of Appeal was unsure whether trade

mark registration of public domain works might, under certain circumstances [notably when the artwork in question is well-known and has

significant cultural value], be against

“public policy or accepted principles of morality” and thus fall within the

absolute ground for refusal within Article 3(1)(f) of the Trade Mark Directive.

The Board of Appeal decided

to seek guidance on this point (as well as interpretation of Articles

3(1)(e)(iii), 3(1)(c), and 3(1)(b) of the Trade Mark Directive) from the

EFTA Court. In my view the most

interesting part of the judgment is indeed the one concerning refusal of

registration on public policy/morality grounds.

|

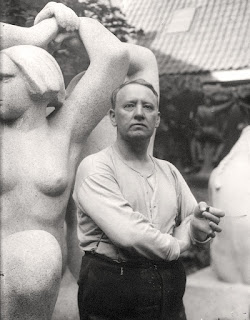

Norwegian sculptor

Gustav Vigeland |

The role of the public

domain in copyright

In addressing this issue,

the Court noted at the outset that copyright and trade mark law pursue

different aims and, in principle, nothing prevents both rights from subsisting

simultaneously [para 62].

With specific regard to

copyright, the rationale of having a limited duration is to serve the

principles of legal certainty and protection of legitimate expectations, but is

also functional - to some extent – to fulfilling the general interest in

protecting creations of the mind from commercial greed and ensuring the freedom of the arts [para

65].

More specifically,

“The

public domain entails the absence of individual protection for, or exclusive

rights to, a work. Once communicated, creative content belongs, as a matter of

principle, to the public domain. In other words, the fact that works are part

of the public domain is not a consequence of the lapse of copyright protection.

Rather, protection is the exception to the rule that creative content becomes

part of the public domain once communicated.” [para 66]

Trade mark protection

Turning to trade mark law,

the EFTA Court observed that trade mark protection intends to ensure market

transparency and assumes an essential role in a system of undistorted competition [para 67]. It is to fulfill these

functions that trade mark protection is potentially indefinite [para 68].

Having said so, however,

because of “the potentially everlasting exclusivity afforded to the proprietor

of a trade mark, there are several conditions that must be fulfilled in order

for the trade mark to be registered” [para 69].

Trade marks for out-of-copyright

works

Turning to consideration of

the specific case at issue, the Court found that a trade mark based entirely on

copyright-protected work presents “a certain risk of monopolisation of the sign

for a specific purpose, as it grants the mark’s proprietor such exclusivity and

permanence of exploitation which not even the author of the work or his estate

enjoyed” [para 70, also referring to

paragraph 52 in the 2003 Opinion of Advocate General (AG) Ruiz-Járabo Colomer in Shield

Mark].

Hence (in principle),

“The

interest in safeguarding the public domain … speaks in favour of the absence of

individual protection for, or exclusive rights to, the artwork on which the

mark is based.” [para 72]

|

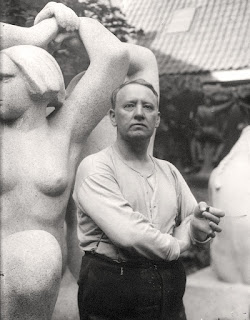

One of the artworks that Oslo municipality

is trying to have registered as a trade mark:

The Angry Boy (Sinnataggen) |

The rationale of the

various absolute grounds for refusal of registration

According to the Court this

also follows from consideration of how Article 3(1)(b) to (e) of the Trade Mark

Directive acknowledges the need to keep a sign available for general use [para 73, referring to paragraphs 33 ff in the 2008 Opinion of AG Ruiz-Járabo Colomer in Adidas]. Having said so, it is possible that distinctive character

is acquired through use, thus paving the way to registration of a sign that ab

initio would have not been otherwise eligible for protection as a

trade mark. Thus, the grounds for refusal sub Article 3(1)(b)-(d) do not ensure

that a certain sign is generally kept free for use over time.

Unlike the absolute grounds

for refusal sub Article 3(1)(b)-(d), the absolute ground relating to shapes

(Article 3(1)(e) of the Trade Mark Directive) cannot be overcome by acquired distinctiveness [para 79] and,

overall, “it overwhelmingly seeks to protect competition” [para 80, referring to paragraph 74 in the 2010 Opinion of AG Mengozzi in Lego].

The role of public policy/morality as an absolute ground for

refusal

Turning to Article 3(1)(f) of the Trade Mark Directive, the EFTA

Court noted that the absolute ground therein is somewhat more ‘absolute’ than

Article 3(1)(e) in that it does not require consideration of the classes of

goods and services for which registration is sought [paras 81-82].

The Court then observed that Article 3(1)(f) refers to public

policy and morality: while in certain cases these two limbs

may overlap [para 85], these concepts are not synonyms:

“refusal

based on grounds of “public policy” must be based on an assessment of objective

criteria whereas an objection to a trade mark based on “accepted principles of

morality” concerns an assessment of subjective values.” [para 86]

In the present case, both

public interest and morality could be at stake.

(i) Contrary to “accepted

principles of morality”

Although the signs for

which registration is sought by the Oslo Municipality would not be “offending

by their nature a reasonable consumer with average sensitivity and tolerance thresholds” [para 91], trade mark registration

of artworks that are considered part of a certain nation’s cultural heritage

and values might be perceived by the average consumer as

offensive, and therefore be contrary to accepted principles of morality [para 92].

(ii) Contrary to “public

policy”

According to the EFTA

Court, “the notion of “public policy” refers to principles and standards

regarded to be of a fundamental concern to the State and the whole of society.” [para 94] As the

understanding of ‘public policy’ may vary from country to country and change

over time, refusal of registration on this ground can only occur in exceptional circumstances. More

specifically,

“An

artwork may be refused registration, for example, under the circumstances that

its registration is regarded as a genuine and serious threat to certain

fundamental values or where the need to safeguard the public domain, itself, is considered a fundamental interest of society.” [para 96]

Having provided a series of

examples, the EFTA Court concluded that:

“registration

of a sign may only be refused on basis of the public policy exception provided

for in Article 3(1)(f) of the Trade Mark Directive if the sign consists

exclusively of a work pertaining to the public domain and the registration of

this sign constitutes a genuine and sufficiently serious threat to a

fundamental interest of society.”

Comment

When

discussing absolute grounds for refusal of trade mark registration in the

context of overlapping IP rights, it is often recalled that in his Opinion in Philips AG

Ruiz-Jarabo Colomer observed that [paragraph

30] a trade mark cannot

serve to extend the life of other rights which the legislature has sought to

make subject to limited periods.

While

this statement specifically referred to patents and designs, in my view one

should be careful not to vest it with a peremptory character that it does not

really have, especially as far as: (1) copyright and trade mark protection are

concerned; and (2) in relation to the absolute ground for refusal within

Article 3(1)(f) of the Trade Mark Directive. In this sense, the EFTA Court was

correct in stressing the exceptional character of this absolute ground for

refusal of registration.

In holding that

registration as a trade mark of public domain work is not per se contrary to public

policy or accepted principles of morality, the EFTA Court achieved what seems

to be a sensible conclusion. This is particular so with regard to the

emphasis that the Court placed on the need to consider the status or perception of the artwork at issue in the country where registration is sought. In

this sense, “the risk of misappropriation or desecration

of a work” may be a relevant consideration in certain, specific instances.

Reviewed by Eleonora Rosati

on

Saturday, April 08, 2017

Rating:

Reviewed by Eleonora Rosati

on

Saturday, April 08, 2017

Rating:

![[GuestPost] G1/24: Tuning in! A take on the state of proceedings before oral proceedings](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjZhEivE5bp7QOwZsyZXAXbVNYSmLjUthkB2Q7fm1_dpB97u5lIQeyWT9ZadUTAH3Z-hXn13VpW4vBDRPx9emCnoDV6tbUTkyvfmqPv1nNInL8XMdrAtSZ2hcRQr2LjxKovC9wTk_XyZxQ0CtX1MUrO_Muz3OJ4ld8AftymsdUmKD7xNksYMwk6/s150/Picture%201.png)

![[Guest post] ‘Ghiblification’ and the Moral Wrongs of U.S. Copyright Law](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhxl1BQBAW3Y-asjb1xXB9eA4DYy77fky6WgR-prC-_6DeBbDqOgCUDWyiz0Q3B23MWWAXnkbS2H2js7OUwA0JQXAHmsyVFgGIHeJz7zJ791vTzOD-4SJqWFIuywFXQyd3ahybbdZd4e8IEVfcNqctvyR8lumv_Gix6Tsw5cSvbHpTI1nwvztDuAQ/s150/IMG_2179.HEIC)

I wonder if Disney could legitimately claim trademark on the image of Mickey Mouse? Currently they have the US copyright term extended each time the original cartoon is about to bcome public domain.

ReplyDeleteIn a consultation on IP in Canada, I recommended that extending design patents to cover characters might be appropriate: I wonder if trademark would suffice?

--dave

By reading the judgment and from an EU perspective, it would appear that a case like this would not fall under the absolute ground for refusal based on public policy/morality. I guess the argument might be more one of distinctiveness or lack thereof.

ReplyDelete