It is simply not possible, from the portrait on her website, to know the size of

Doctor Nicola Searle, resident Katonomist of this Cyber-Parish. However, her first subject this week is growth -- something which both humans and felines generally experience without the need for any incentives (this week's second subject). The economics of incentive-led growth (or is it the growth of incentive-led economics?) sounds like the sort of thing that gets written into the first couple of sentences of

every a Ministerial speech on the value of intellectual property, so it's good for readers of this weblog to have a least some passing knowledge of what the juxtaposition of those terms means to a real economist. Anyway, this is what Doctor Nic prescribes for the IPKat's patient readers:

"If IP is about creating an incentive to innovate, and we desire

innovation because it increases economic growth and development, then what is

the relationship between IP and economic growth? This is a fairly important question. After all, the Google quote behind the Hargreaves review implies that IP is a barrier to innovation.

On the flip side, we have arguments that strengthening IP systems will lead

to growth as in the case of the patent box or enforcement of copyright.

This relationship between growth and IP could be

positive or negative (or the relationship doesn’t exist, but that doesn’t make for a very good

post). Readers will forgive a Katonomist

for indulging in graphs to illustrate the potential relationship (adapted from

here).

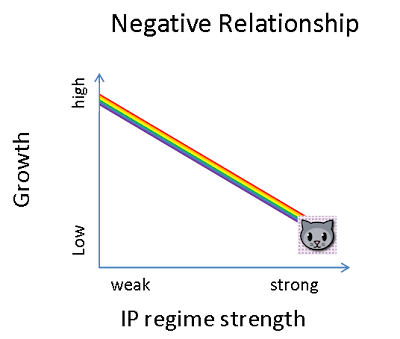

If the relationship is positive, then economic growth

increases as IP increases in strength or enforcement. Likewise, a decrease in IP strength will

result in a decrease in economic growth. This is the main argument behind the economic

incentive theory of IP – stronger IP encourages more innovation which leads to

more growth. As my

Nyan Cat-inspired graph shows, a stronger IP regime results in higher growth.

German and Austrian economists

Schafer and

Schneider develop a

model which predicts this positive relationship in the context of international

development. They argue that when

developing countries increase their IP enforcement to that of the developed

countries, their growth rates increase.

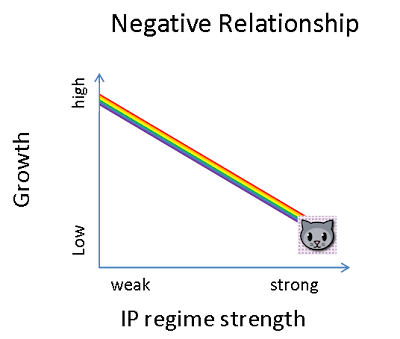

In contrast, if the relationship is negative, then

increasing IP regime strength results in a decrease in economic growth. This supports the Google quote that the UK IP

system inhibits innovation by encumbering R&D and preventing

competition. Weaker IP would allow for a

freer environment and greater diffusion of innovation. It might also decrease incentives for more

strategic types of IP use (such as NPEs) which do not contribute to innovation. The cat goes down.

Boldrin and

Levine argue along these lines in their

book using historical cases where increased IP strength did not increase innovation

and growth. They also point out that

most studies merely prove that increases in patent strength simply increases

patenting.

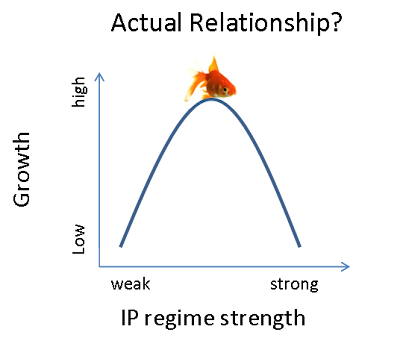

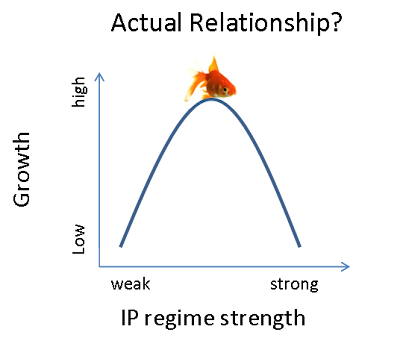

A third, magical option is a combination of the two where

there exists an optimal level of IP strength.

Too strong and you inhibit innovation.

Too weak and the incentives to innovate don’t work. This optimal level of IP protection

(indicated by the goldfish) balances these competing forces and serves to

enable economic growth and development.

American based

Davis and

Sener argue this upside-down-U shape relationship between IP enforcement and innovation.

That is the theory.

What does the evidence say?

The gold standard in economic evidence of IP strength is the

Park and Ginarte index. Their index, created

in

1997 and updated in

2008,

measures the strength of IP protection in countries by looking at patent

coverage, membership in international organisations, provisions for loss of

protection, enforcement mechanisms and duration. For example, in the 1997

version, the UK scored a 3.26 out of a possible 5 and Brazil scored 1.52. In 2008, the UK scored 4.54 and Brazil,

having joined TRIPS, scored 3.59.

In their 1997 work, Park and Ginarte found that stronger IP

enforcement had a positive impact on R&D in developed countries but not in

developing countries. They point that

this could be a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem – as R&D grows and becomes

more profitable, development of IP systems also grows. Another possibility is

that R&D activity in developing countries is largely imitative and

therefore not potentially patentable.

Additional work also supports the positive relationship

between IP strength and growth. Americans

McLennan and

Le use software piracy as a proxy for the level of IP strength in a country and find

that stronger IP is associated with higher growth rates. Likewise, UK and China-based economists

Chu,

Leung and

Tang argue that increased patent protection in the

US reduced the volatility of growth.

Other researchers find that relationship is not positive. Harvard

economist

Lerner examines UK patent filing around the world. He

does not find a relationship between strengthened IP policy and

innovation. However, he notes that the

measurements available are relatively crude and the time frame of analysis may

be too short. Nonetheless, he describes

the lack of the relationship between stronger patent protection and domestic

patenting as striking.

An American-based

Schneider finds,

using patent data as a proxy for innovation, that increased IPR enforcement

leads to more innovation in developed countries but less in developing

countries. She, like Lerner, notes that there are challenges to the data and,

in particular, to data surrounding IPR as its effect on growth is indirect.

It is not easy to study the relationship between IP and

growth. Separating IP regime strength from other factors such as institutional

strength, innovative capacity and social norms is difficult. Measuring

innovation has long plagued researchers.

The studies reported here focus on patent with little evidence for the

relationship between other types of IPR and growth. What if the evidence shows

correlation and not causation?

The inconclusive evidence is potentially consistent with an

inverted-U shaped relationship between IP and growth. Somehow, we have to find the balance between

the tragedy of the commons,

where property rights improve outcomes, and the tragedy of the anti-commons,

where property rights encumber progress.

Are all IP debates about the location of the goldfish?"

Goldfish recipes, for those

who eat fish and for

those who don't.

Reviewed by Jeremy

on

Monday, May 14, 2012

Rating:

Reviewed by Jeremy

on

Monday, May 14, 2012

Rating:

![[GuestPost] G1/24: Tuning in! A take on the state of proceedings before oral proceedings](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjZhEivE5bp7QOwZsyZXAXbVNYSmLjUthkB2Q7fm1_dpB97u5lIQeyWT9ZadUTAH3Z-hXn13VpW4vBDRPx9emCnoDV6tbUTkyvfmqPv1nNInL8XMdrAtSZ2hcRQr2LjxKovC9wTk_XyZxQ0CtX1MUrO_Muz3OJ4ld8AftymsdUmKD7xNksYMwk6/s150/Picture%201.png)

![[Guest post] ‘Ghiblification’ and the Moral Wrongs of U.S. Copyright Law](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhxl1BQBAW3Y-asjb1xXB9eA4DYy77fky6WgR-prC-_6DeBbDqOgCUDWyiz0Q3B23MWWAXnkbS2H2js7OUwA0JQXAHmsyVFgGIHeJz7zJ791vTzOD-4SJqWFIuywFXQyd3ahybbdZd4e8IEVfcNqctvyR8lumv_Gix6Tsw5cSvbHpTI1nwvztDuAQ/s150/IMG_2179.HEIC)

![[Guest book review] The Handbook of Fashion Law (with a discount code)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgB4h2AdqJKwq9O3Ft4Mb7C39tv_NeFpkzrOfvhIsuwAkM_ops2Hgj7fdwzq_TQsjQDvQrQa-yyC9Q9pNiugseXRlUaMdsr_cmYUbh9lH8HDECMCbsTuNboVgpafyEhkgDkVS6ruHkuz8Sx0QVGI_1S8R9kbsHdNIYrRjqhyphenhyphen010_txjJUYvlZOtWA/s150/Fashion%20Law%20Book%20Bicture.jpg)

The relationship between IPRs and economic growth is extremely complex.

ReplyDeleteThis is due to many reasons, one of them is that here we are talking about intangible assets.

I believe that there is a connection between the two. I disagree that IPRs stop growth by limiting competition. On the contrary I think that patents encourage economic development. When we have a patented technology it can be used only by the owner. But this is some kind of stimulus for another market participants to look for new ways for using this technology or for creating new one.

So the barriers imposed by patents stimulate R & D. Without IPRs every market participant will use what he wants but this means that nobody will win. A situation in which everybody win is not possible in the real economy.

In a world so heterogenous and so fast-changing, and with so many factors affecting economic growth, it's simply silly to hope to demonstrate that IP is good (or bad) for growth or to try to calculate a "optimum amount" of IP for something else than a certain situation in a certain country at a certain moment. And even then, so many assumptions and simplifications would have to be made that nobody would be convinced anyway.

ReplyDeleteIf reality "doesn't make for a very good post" (or does not help to sell many books about IP or economic growth), then I'd prefer that you write about something else.

The debate about IP is largely, if not exclusively, a political one, like on taxes. It's about: which group do you want to favour ?

Jeremy, I particularly like your links to Wikipedia on the opposing tragedies of the commons and the anti-commons. Scylla and Charybdis. How to sail between them, so that innovation in Europe advances, will be the business of the Central Division of the new EU Patents Court. If it is sited on the mainland though, will it have the nerve, and the navigational tools, to get all its cases through the channel? I see black. Sorry, but I imagine most every one of its cases foundering on one rock or the other.

ReplyDeleteSome problems here.

ReplyDeleteInnovation. What is that? IP "strength"??? IP "regime strength"???

As a general rule the development of an effective IP system precedes increases in R&D spend and not the contrary.

This is a simplistic US view of IP and its impact or not on innovation, growth and economic activity. You need to take into account. Quality. Quality of the IP granting system, quality of the courts, quality of the applicants, quality of the underlying R&D, quality of the "innovators".

It's not static. One day software patents are verboten next day they are the bee’s knees. Those changes really screw analysis by economists. One day “strong” next day “weak” next day “strong” again. Flip Flop.

Politics drives these effects as does anti-competitive bevaviour. The dominant position of US companies in software/internet etc has everything to do with abuse of an IP system and not the IP system itself. Google was not complaining about the system per see but its abuse. Corporate abuse supported by politicains in a countries self-interets will always hamper innovation by foreigners. The NPE phenomena is a reaction to the anti-competitive behaviour of corporate America, which has abused and missued SME and small guy invention and innovation for decades.

So when you hear the cry. “Patents are a barrier to Innovation.” Read “The effective enforcement of SME and small guy patents through NPE entities is really p*****g me off.” The Economists need to try and distinguish between innovation and IP theft.